David Hudson opened the door to his traditional Queenslander home back in 1988 and welcomed us inside. Glad to be in out of the heat, we made our way to the cool centre of the house. He told us to make ourselves comfortable in the small sitting room while he went to the kitchen; he returned, swiftly, with chamomile tea for us and sweetened black tea for himself. We passed a few more moments in small talk, then, with something of a ceremonial flourish, he produced the reason for our visit from underneath his chair. “She’s a solid. I reckon she’s a beauty,” he said to me as he handed “her” over.

“She” was a didgeridoo, a musical instrument cut and fashioned from trees after termites have chewed out the insides, making the trunk hollow. The one I held was about three-and-a-half-feet long and painted in traditional red ochre, black, and white colours. As I turned the beautiful, soft thing ‘round and ‘round in my hands, David gave us a cultural lesson, pointing to the images he’d painted on the sides.

“There, the black dots?” he said. “For the people of the land, my people.”

His people on his father’s side are the Ewamian; the Yalanji are on his mother’s. Both areas are prolific in Aboriginal rock art. David’s love for that is clearly expressed in his voice whenever he speaks about it. Ewamian is also volcanic with many underground lava tunnels, tunnels formed 180,000 years ago.

He continued on, explaining the didge symbols:

“This, the red ochre,” and he got very quiet, “this is for the blood that was shed, the blood of my people’s suffering—and of the political struggle that we still face.”

And so it went, each image significant to him, given new meaning for us:

“This, the white paint that surrounds each image, this is the air we breathe.”

“This, this is Gorialla, the mother rainbow serpent who created the world.”

“And the goanna, that is ‘Gunyal,’ a true lizard of Oz.”

Finally, he pointed to the two feet he’d added along one side and said, “That is for you fellas, on walkabout.”

This startled me, his acknowledgement of us that way. Walkabout dreaming had kept me alive, kept me fighting to recover from a near-fatal illness. When told by doctors I could never trust my health again, that was it. It was time to go, before it was too late.

We quit our jobs, sold our house, and left Canada to explore this amazing culture for six whole months. The term walkabout has its origins in the indigenous Australians of old, who would leave their homes to wander and visit new places.

I’ve always loved to wander. My father says it’s because we have gypsy blood on his side of the family. My mother scoffs and explains it’s the moors on her side that gives me my itchy feet. Whatever the source, I regard this trait as coming from the deepest spiritual part of me.

We had only just met David Hudson the day before, travelling from Cairns to see his troupe perform in Kuranda. In those days, Kuranda was reached by road or by a picturesque, heritage train. David says there’s a modern gondola that goes up over the rain forest to Kuranda now, as well.

In 1988, we took the little train through the exotic countryside and arrived to a languid town, sleepy, in spite of the crowds of tourists. At a busy market we bought our lunch and sat on the theatre steps in the warm shade, munching on shellfish and waiting for the show to start. Somewhere, someone was broadcasting Australian bush ballads over a loudspeaker. In my notes I was silenced, reduced to describing that indelible morning in a cliché: I thought I’d died and gone to heaven.

Shortly after that, sated from a lunch of prawns, I innocently took my seat in the cool, darkened room of the tiny theatre. I left the building an hour later, bemused. It would be many years before I would feel the kiss my sleeping unconscious mind received that day. Years before I would begin to awaken from the duty-induced stupor I was in.

I remember I had looked at the stage as the theatre darkened and felt time become a kind of spacious present. It was a deeply sensual and disturbing 45 minutes.

David was one of the performers who danced, sang, told stories, and made us all laugh. Never once insulting the perpetrators of the issues they’d endured, the storytellers focused on building understanding of our cultural differences.

I wept more than once, moved by forces of longing, and a sensation of guilt I didn’t understand.

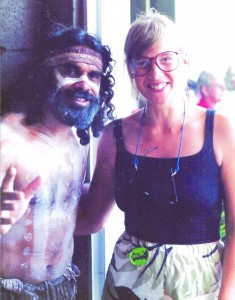

After the show I insisted we try to speak to these astonishing people and planted myself beside the stage. We spoke to the group of male dancers, who cheerfully answered all my touristy questions.

My journals mention my insatiable need to hear pronunciations, which at the time I tried to write as many down as possible. At one point, when one man was telling me how my beloved didges were made, he paused, looked at me and grinning, joked, “The didgeridoo—oi! That’s ‘didgeradoo’ in Australian!”

The experience made me long to explore the indigenous culture around Cairns and Kakadu, but I was constrained by time. While on this trip (and not obedient to true walkabout law) our schedule was often dictated by our daily mileage.

So, when David asked if we could hang around for a couple of days, I crossed my fingers behind my back and lied. “Sure we can,” I said. “We’re fairly open.” I was hoping we could recoup the lost time somewhere down the road.

“Give me a couple days? I can make a great didge for you and for half the price of what you’ll pay in the tourist shops,” he said.

We agreed to meet him in two days at a place called The Gallery Upstairs in Cairns.

We passed the time exploring the region.

Climbing to the Atherton Tablelands I saw my first fig trees, the parasite long ago killing its host, and touched a massive Kauri pine. We took in an art gallery in rambling Yungaburra and drove through a lot of farmland. When both people and car began to overheat, we turned our faithful Ford Falcon’s nose back to Cairns. The guidebook recommended a beautiful swimming hole at Davies Creek. At the end of about five kilometres of washed out, washboard road, wine in hand, I sank, thankfully, into the Eden-like pools.

Promptly 48 hours later, we presented ourselves at the gallery (now no longer there); we were told neither Hudson nor the didgeridoo were there. We were sent on to his home in a suburb of Edge Hill. That day his face was clear of the ribbons of white grease paint but that only seemed to increase the smoky depths of his eyes, under thick black brows. His smile was the same intense show of both sets of teeth and still with that strange mixture of friendly caution. The lower half of his face was covered in a thick beard; so black it shone blue, as did the long, heavy coils of shoulder-length curls.

And, oh! The colour of his skin. It ranged through an entire spectrum of richly highlighted plains of sepia smudged by burnt umber. Trying not to stare, I sized up the man.

David is my height, 5’7,” with a lithe, softly muscular form. In current photos, I was unreasonably pleased to see he’d kept himself in good shape all these years. I knew from the revealing costume he’d worn the day of the performance, his chest was adorned with just enough hair, and formed a black plate that arrowed down to a tightly packed torso. I looked up into his eyes. They twinkled with good humour as he noticed my assessment of him. He grinned good-naturedly, and winked. I looked away, unsettled by this charismatic man.

He asked us if we’d like him to play something. “Please,” I breathed, like some awestruck groupie. Clearing my throat, I tried again. “That’d be great, thanks.”

He stood up and stepped towards me, laying the didge in the dip near my shoulder. He leaned back, angling the tunnel, and with puffed cheeks, blew into the opening.

A didgeradoo player breathes in a circular fashion, in through the nose and out through the mouth in an unending stream. The vibrating wind sounds filled the tiny room, and I was enthralled. I stood, afraid to move, lest I break the spell. The didge was communicating with me! The room suddenly seemed as big as the universe.

The player moved us from a sense of mourning, to a happy kangaroo hopping by, and ended with the joy of lovers—an extended moment in which a lifetime could be lived. How did it come to be that I was standing here in a stranger’s living room while he played didge with my clavicle? My hands went up to my face, to cover my warm cheeks.

It is impossible to describe David Hudson without referring to his music and his art. When he plays his guitar, or haunts us on the didge, the man disappears into the background and the music comes through—like a conduit connecting the past to the future.

His singing voice is as melodic and as sound as the stories he tells. His didge playing reminds me of the vibrations that tie us all together, while his guitar strums the framework.

He is an artist whose work includes his paintings, which explore the dreams and symbols of his people.

He hunts for his own wood to make his didges with. I find his creative energy infectious, prompting me to get out my own paints and try my hand at a dream sequence of my own.

His Aussie name, Dahwurr, means “black palm,” which he tells me is “a strong hardwood, tall and straight and good for spears.” This stately tree also has a beautiful wood grain. Details which, in part, lay an apt description of the man himself.

He was Dwura when I knew him, but he said he changed it to Dahwurr because too many people had trouble pronouncing Dwura. Again, he works to communicate: if his name is a barrier, he selflessly modifies it to make things easier for others.

David’s English sounds pretty much the way an English Canadian speaks—if you don’t count the colourful substitutes for just about every noun, not to mention the distinctly irreverent goofing around with the King’s English. Australians in general speak in a kind of clever shorthand: “beauty” is “beaut,” “good day” is “g’day,” and, as near as I can figure it, to “believe, think or concur” is summed up simply as “I reckon.” And, of course, “didgeradoo” is the delectable “didge.”

My toes curled with pleasure in anticipation of a dropped “h” or a deliciously elongated “e.” And as far as his transitions go, he doesn’t waste breath with tiresome verbal phrases and prepositions.

Hudson had roamed far since I sat in his living room drinking tea. His life expanded into acting, television documentaries, and travelling extensively for his music, even performing with Yanni at one point. I enjoyed catching up on his work via the internet, and to see his smile was the same grin beneath those intense eyes.

But why, back in 1988, had he gone to such ambassadorial lengths for two wandering strangers? Strangers, who, like others before them, hadn’t asked for permission to stray through his ancestral backyard. Hudson will say it’s because he works to bridge cultures, using creative expression as tools for teaching peaceful coexistence.

Today, I paused in my writing to reach across my desk and take hold of my didgeradoo beauty, my little “beaut.” I love the feel of softness as my fingers lightly trace the familiar images. I always knew she was a work of art, but I hadn’t appreciated that she is also a bridge, a bridge to other cultures, to the past, and into the future. Hudson says what he does is “cultural edutaining,” explaining that he is an entertainer dedicated to educating people from all walks of life on the proud, indigenous Aussie.

They are a strongly independent people from an ancient culture, who want to tell their stories through their music, art, their dances, and their politics.

Hudson once said that cultural tourism means expressing his living culture every day to guests from everywhere around the world, and it’s a responsibility he takes seriously.

And to that I say, good on yer, Dahwurr.

Good on yer.