“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.”

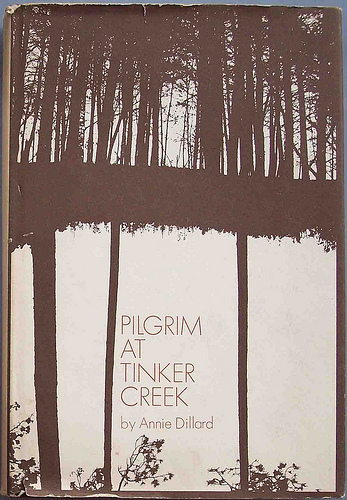

So said Annie Dillard, an American writer most famous for Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, a non-fiction narrative about a year spent living in the mountains of Virginia. The writing style, infused with poetic descriptions of insects, frogs, mountains, and weather, became instantly identified with her and her mystical vision of the world. When she won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975, she was catapulted to instant literary fame.

It was a fame that she spent the rest of her writing life trying to flee from.

Despite her public reserve, Dillard’s non-fiction books are both deeply personal and emotionally universal, exploring questions of philosophy, metaphysics, science, and whether or not God exists. But, in the grand tradition of the essay, she avoids coming to conclusions.

“All my books are a series of questions,” she once said, believing that it is the role of the artist not to answer questions, but to point readers in a direction where they might find answers for themselves.

The format of her questions are often explorations of the natural world and all its diversity, written with a refreshing lack of sentimentality. And although she writes what she calls non-fiction, Dillard never hesitates to, in her words, “fiddle with the facts” to attain the emotional effect she is aiming for.

The effect is emotional transcendence, in which everyday objects and encounters point past the mundane towards the full potential of our human spirit. If we spend our days in wonder, we will lead lives that are wonder-filled.

Her meditations on moments of ecstatic transformation show the changes in herself, as well as in the way she sees the world. But she doesn’t force this revelation on us. She takes us along for the ride, and in the end we are left holding a new way of seeing ourselves.

Annie Dillard must-read:

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

(Lansdowne library code: QH 81 D56)