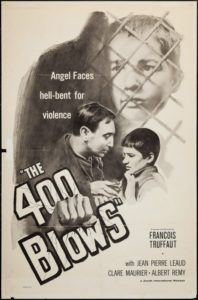

The 400 Blows

5/5

François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) is not a film for those just getting home from a night of debauchery; if you’re reading this while you sip gingerly on a cup of coffee, I advise that you turn to the hangover’s best friend, Netflix. This isn’t a film for a casual viddy or for a last-minute perusal.

The 400 Blows is a 1959 black-and-white French film (yes, with subtitles) about a young boy (played masterfully by a 14-year-old Jean-Pierre Léaud) struggling to grow up in world dominated by domineering adults. But if you can find it in yourself to take the time and use your mind to digest what Truffaut is saying—and how he says it—you’ll have discovered pure cinematic poetry.

This is a film for people who appreciate the deceptively simple and the silent beauty in the unsaid. For example, Truffaut guides us serenely through the winding, cobbled Parisian streets, and we’re left with the feeling that this film is in a perpetual state of early morning; the streets rarely bustle, but instead lie in wait for Truffaut’s camera to glide down them. It gives the film an intangible beauty that at the same time carries with it the cruelty that can be life.

That said, The 400 Blows is also peppered with humour (following a 14-year-old boy around is guaranteed to produce a few laughs), and often the viewer is swept away in the various hijinks that ensue. Truffaut has a keen eye for boyhood antics, and it makes perfect sense that The 400 Blows is semi-autobiographical.

The film’s score—composed gorgeously by Jean Constantin—meshes the poignant and the peppy. There might have been a slight disconnect in the film, as it juxtaposes youthful exuberance and familial strife, but Constantin’s score is able to bring both halves of the film together perfectly. Music is able to much more easily shift from sadness to happiness than a film is because it has no plot restraints—it’s abstract—but when placed alongside the structure of a film, music’s abstraction is able to attach itself to the plot of the film and lend the emotions it evokes to the film’s story.

The 400 Blows is a great-grandfather to modern films like Boyhood (2014), where plot is forgone for feeling. Both films follow a boy’s evolution through childhood, and although they tell specific stories of specific people, they’re also able to touch on elements of growing up that resonate with everybody.

However, like poetry, The 400 Blows gives little more than what you are willing to put into it; if you want merely to zone out, I suggest the new season of BoJack Horseman. If you want a film that can make you really feel something, The 400 Blows is just the ticket.