Megan Quigley graduated from Camosun’s Visual Arts program last year and is now bringing her skills back to campus through Camosun’s Van den Brink residency.

The residency allows a graduate from the last three years of the Camosun Visual Arts department to work on a project for two months with access to the college’s art studios.

Quigley says that the project—which is called Mother Tongue and will be on display in the foyer of room 117 in the Young Building on Lansdowne campus until October 14—is “an investigation of the process of learning language.”

“[It’s] a process of negotiating cultural identity, diaspora, and a relationship to place,” says Quigley.

Quigley’s artistic medium of choice includes embroidery onto tarp; she says that she’s really interested in how materials relate to a process.

“I’m less interested in creating objects that maybe present themselves as art objects,” she says, “and rather more interested in understanding how material has a certain reference or a certain memory to it.”

Due to the tactile nature of what she does, Quigley says she has always had a soft spot for construction materials and how they can intertwine with and act as an aid to “the process of transition.”

“I think that the way in which—specifically in Victoria—one might relate to construction materials is if you’re walking down the street, for example, and you encounter a building that is being demolished or being built, and you see tarps or you see displaced ground,” she says. “It makes you conscientious of the fact that the place that you’re in is in flux, and is also constructed and built.”

As far as how that lends itself to her process as an artist, Quigley says that the city she lives in, the ground she walks on, and the buildings she sees can “call attention to the different processes that transform our relationship to place.”

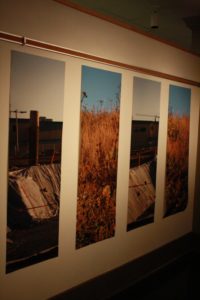

Quigley has combined some of the materials in her project that she sees in construction zones, such as tarp and Tyvek, with photography of the city. But even with something as basic as landscape photography, Quigley puts her own creative spin on things.

“Instead of going and taking pictures of the landscape, I’ve done a series of durational videos,” she says. “I’m presenting it as a still, but one that is also kind of breathing.”

Quigley says that it is a “slippery line” between a durational photograph and a durational video.

“It’s just a straight shot, so there’s no camera movement, and there’s not a lot of movement in the subject,” says Quigley. “In this way, it might have more of the characteristics of a photograph, but it’s still a video.”

The video in this case—of a cliff along Dallas Road—is still for the most part, but it has, as Quigley puts it, “glimmers of movement,” such as water and wind rustling trees. Quigley says that she is really interested in addressing the boundaries between video and still shots.

“I’m really interested in notions of hybridity as they relate to material, but also how that can then broach into conversations of locations and identity.”