Attending a post-secondary institution is not just about making it to class on time, double-spacing your mid-term paper, and choking down cafeteria food. Those are elements of a student’s day-to-day life—some of them vital elements—but education sometimes comes when a chalkboard is nowhere in sight, as it did for me the foggy fall Friday afternoon I sat in John Threlfall’s office at the University of Victoria.

Threlfall is the special projects and communications officer for UVic’s Faculty of Fine Arts.

He’s also a witch.

Threlfall isn’t comparable to any post-secondary employee I’ve ever met. His office is covered in pop-culture memorabilia, including a vintage orange-soda poster, of all things. He is also a man of peace, spirituality, and religion, something that he discovered in 1986 after living a childhood that consisted of no religion (“except maybe consumerism,” he says). For the past 30 years, Threlfall’s religion of choice has been witchcraft, which, he says, is tragically misunderstood.

Finding peace and belonging

“I’m going to bundle it all up into a ball and light it on fire and release that energy out, and then this new energy, I’m going to write it on a piece of seed-based paper, and then put that in the ground so it grows, and as that grows, the energy is attracted to me.”

Threlfall is explaining one of his spiritual practices as a witch. The bundle of fire, for him, in this example, represents the obstacle, the entity from which he is seeking solace, by literally eliminating it to ash and replacing it with something more desirable.

The “seed-based paper” is the solution, the object in the Earth that will help him reach his goal; the specific goal is not relevant to understanding the spiritual practice. Witchcraft doesn’t follow scripture. Instead, it draws on the five elements (earth, water, air, fire, and spirit) to honour nature, which is the basis for the religion.

“I’ve had rituals with people where we cook together,” says Threlfall, who adds that all rituals, for him, begin in a circle. “You get together as a group, you open the circle… and you cook. And as you put things into—literally—the soup pot, everyone’s adding things, they’re adding their energy, they’re adding ingredients. You have intention. You’re stirring it up and then you all eat the soup together and take that into yourself. We’ve also done really silly rituals where we toss oranges at each other to represent the sun going through the sky. It’s sometimes silly, sometimes fun, sometimes serious, sometimes sombre; it’s a little bit of everything.”

Linda Beet is a local tarot-card reader and a witch who practices in the area of reclaiming, a witchcraft tradition that brings together politics and spirit. Beet finds the cultural misunderstanding of witchcraft “cute” and says that it shows that humans often are repulsed by the offbeat, or by severe difference. She says that anti-witch discrimination can get to the point where people lose their jobs over being involved in witchcraft, causing some witches to stay closeted, or, as she puts it, “not out of the broom cupboard.”

“The fear that people have isn’t just based on stigma and depictions,” says Beet. “I think there is also a cultural fear of non-conformity, a cultural fear of difference, and we see that in every category of how we can be different. And this is how you can be very spiritually different. There is a lot of ignorance and assumptions out there. I think this is one of the reasons not a lot of witchcraft is public.”

One of the more common misconceptions about the religion is that it is Satanistic or evil in nature; in reality, says Beet, it is about peace and acceptance for most. She adds that Satan is a traditional devil in Christian beliefs and, in fact, has nothing to do with witchcraft.

“The Judeo-Christian model of ‘we work to be able to leave our bodies and go to a happier place’… it doesn’t make the slightest bit of sense,” she says. “It doesn’t connect to what we do at all as witches.”

Beet says that lesser-known forms of religion and spirituality can be confusing to someone who practices a more mainstream religion like Christianity; when the beliefs of others clash with the beliefs they have carried their whole life, it can be hard to understand at first.

“What if we’re right?” asks Beet. “What if we can just talk to spirits, what if we can see through time, what if we can make magic happen? That messes up a lot of firmly held philosophical and theological beliefs for a lot of people.”

Beet says she understands how one might react in an uncomprehending or even hostile way when it comes to being involved in what many consider to be a left-field spirituality.

“It’s harder to accept someone who practices and believes something which is diametrically opposed to your own belief system, your own worldview,” says Beet; she adds that witchcraft entails a lot more flexibility than other practices because of the lack of designated scripture, such as a bible, or other strict guidelines, although there are numerous books on the religion.

The portrayal of witches in popular culture, says Beet, has definitely not always been accurate, but she says it can be entertaining. She points to True Blood, saying it was fun to watch but completely inaccurate as to what she actually does as a witch. She also says some people started practicing initially because they were attracted to the way the Harry Potter series portrayed witches. (Of course, Lawrence Pazder’s infamous and more or less debunked Michelle Remembers, a book claiming to be a true story associating local witches with Satanism, didn’t help, given the hysterical Satanic Panic of the era it was released in.)

“I think it’s a gateway drug. That sort of stuff draws a lot of people in. Witchcraft is a very unique and awesome solitary path,” says Beet. “Even though it tends to be really inaccurate portrayals of witches in media, sometimes it wakes people up and it inspires them and it encourages them to seek out and find other people. We’re finding now that there is a whole wave of young people who are showing up because of Harry Potter and all of the fantasy media that has been proliferating for the last 15 years or so.”

There are multiple metaphysical stores in Victoria, while the lower mainland couldn’t support one, says Beet. So why is Victoria such a powerful metaphysical epicentre for witchcraft?

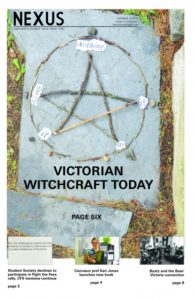

“It’s much more cohesive [than Vancouver],” says Threlfall. “I came to Victoria specifically because I knew it was an outreach town, some place where I could be comfortable, find an open community, wear my pent [pentagram jewelry] walking down the street and not feel alone.”

Back in his office at UVic, Threlfall leans forward in his chair to show me the silver pent hanging around his neck; he says that jewelry and accessories are often a big part of witchcraft.

“There’s no way of recognizing other witches; we don’t have a secret handshake or a secret wave or anything like that, so quite often we rely on jewelry to know.”

Threlfall remembers when Hecate’s Loom, a national pagan magazine, was being published out of Victoria. Things happening in media and politics, he says, help put Victoria on the witchy map. A group called 13th House Mystery School, which Threlfall is a part of and which he refers to as an “umbrella coven,” has been teaching a bi-yearly 13-week how-to class on rituals for almost 20 years. UVic was home to Robin Skelton—“arguably Canada’s most famous witch,” says Threlfall—who co-founded The Malahat Review there and was the founding chairman of the university’s Creative Writing department. It’s reasons like these, Threlfall says, why Victoria often draws in marginalized subcultures.

A witchy lineage

Local witch Alison Skelton, daughter of Robin, says that it’s a misconception that she followed in her father’s footsteps when it comes to spirituality and religion. Skelton says her father did not openly practice witchcraft when she was growing up; they happened to cross metaphysical paths quite independently.

“I grew up in an environment that was conducive to that kind of thing. There was a philosophical awareness of the importance of nature and mysticism,” she says. “It was there but it wasn’t defined as anything. My father didn’t actually define himself as a witch until I was around 17.”

Skelton began taking a tarot-reading class with Victoria’s Jean Kozocari (who co-wrote the 1989 book A Gathering of Ghosts with Robin Skelton) and fell in love with the craft. She began accompanying her father and Kozocari on “ghost-busting” missions throughout the city.

“There are so many things that can be experienced as hauntings that aren’t necessarily what popular culture considers a classic haunting of the spirit of somebody who is dying,” she says. “There are lots of ways that energy can show up as being disruptive or troublesome.”

Skelton says that she would “pick up on emotion” and “get images” that were like seeing past events play out before her eyes. She says she’s not sure what emotions these spirits were feeling, but she would pick up on them.

“I would follow—almost like a dog following a scent—to a point in a building or in a house that felt like that was where the problem was centred,” she says. “Then I would be able to say what it felt like or what images or metaphors came to me.”

For individuals who are curious about the religion, Skelton says that independence—the same independence she used to form a practice separate from her father’s—is key. Skelton says to not rely too much on other people’s ways of practicing.

“Be creative,” she says. “Personalize it. Don’t be afraid to draw on your personal symbolic language to inform you.”

Such language, Skelton says, is shaped by all of the experiences a person has throughout their life. The input from those experiences can then shape your practice, she says.

“That develops in us a symbolic language,” she says, “that the spirit can then communicate to us through.”

A close call behind bars

Michele Favarger is a local witch and a legally ordained priestess. She witnessed the political and legal transformations that make Victoria the harbour in the tempest it is today. She was also the Wiccan chaplain at William Head Institution, where she officiated the marriage of an inmate in a pagan ceremony.

“That happens, you know,” she tells me with a laugh.

The catch is that after she had finished and wedding bands had been exchanged, a marriage commissioner told the newlyweds to remove the rings so he could “marry them properly,” says Favarger.

“The bride looked at him and said, ‘No, we’re already married; you’re here to sign the paperwork,” says Favarger. “I think, actually, her words were something like, ‘Over your dead body.’”

Favarger says it’s hard to see some people brush off “such an Earth-based religion” as though it’s some kind of joke. She says that because the commissioner did not recognize anything but traditional Catholic ceremonies, the wedding was almost ruined.

“The thing is that a marriage commissioner can’t perform a religious ceremony,” says Favarger. “It can only be a civil ceremony. The fact that he chose to be so insensitive to the desires of the family of the bride and the groom, that became very much our reason for getting recognition here in Canada.”

Favarger says the marriage commissioner heeded the words of the bride, stepped down, and allowed the bride and the groom to keep their rings on, subsequently signing the paperwork. But the legal recognition of Wiccan marriage ceremonies “was a far lengthier process.”

“It was a matter of being established as a society,” says Favarger. “It was a matter of proving our record, of showing that we were in service to the community, not only to the local community, but to the broader community.”

Favarger says that proving that the religion met human needs in a spiritual sense, as she had to do get legal recognition, was not an easy process.

“The fact that I was the Wiccan chaplain at William Head for 14 years certainly added to that record, but I had only recently started [at William Head] when we began that process with the church,” she says, adding that the entire process took nearly 25 years.

Now, she can look back on that time of politics, discrimination, and social conservatism with a keen logical analysis of the ins and the outs and the hows and the whys, and, most importantly, derive from it a sense of purpose.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re a priest or priestess, or a minister, or a chaplain,” says Favarger. “Your service is through the gods to the congregation. If I am able to meet the needs of people who are seeking a spiritual connection, then my job is done. And if I can have that recognized in their rights to their own spirituality protected in the eyes of the law, then that’s critical, you know? If you happen to be a practicing Wiccan and you have your children taken away because the government believes that you’re practicing something that’s nefarious, wouldn’t you want to have someone step in and say, ‘No, hang on a second, there is nothing nefarious going on here, we’re simply practicing a very Earth-based tradition’?”

Back in Threlfall’s office at UVic, we’re deep in conversation. He says that for him, a unique form of spirituality filled a void that a consumerist-based, theology-deprived childhood left open. It comforted him, he says, gave him a sense of purpose, and opened up a whole new, peaceful way of seeing the world.

“It was certainly nothing in my family background,” he says. “We were so aggressively middle-class it was crazy. We had no religion at all, so the idea of religion was not even a part of my life, which is one of the reasons, spiritually speaking, I started looking for something, because I didn’t have that.”

But Threlfall knew there was something greater and bigger for him to cling to. He says his family was not surprised when they learned he had become a witch, saying that if he was going to pick up a religion, it was bound to be an interesting one.

“When you’re in your teenage years,” he says, “you start looking for that sense of belonging, sense of community, something greater than yourself. As I read more about 1960s-era cult practices, if you will, it just resonated with me, and it seemed to be the thing that interested me. I liked the idea of incarnation, I liked the idea of—and this was even before George Lucas came up with the idea of the Force—just being connected to other things through energy.”

There was a profound energy about me when I left Threlfall’s office, my consciousness flooded by a new well of spirituality I did not previously know existed. Could it be, I wondered, that witchcraft is the spiritual answer hiding in plain sight that many spend their lives searching for? Maybe, maybe not, but one thing’s for sure: any premature assumptions I had once held about the religion, be it through ignorance or the influence of popular culture, had vanished into the dark October night.