5/5

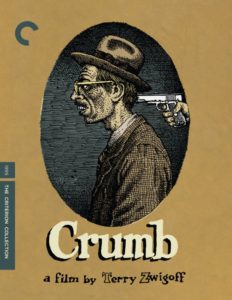

The world of Robert Crumb, the reclusive and reluctant counter-culture comic visionary of the 1960s and ’70s, is a fiercely fascinating microcosm of idiosyncrasies including sordid perversion, familial dysfunction, and the pressures of unwanted fame. Crumb (1994) is the microscope that documents it all, and in doing so it shows us the warped soul of a stymied genius.

Many of Crumb’s scenes are similar in effect to rolling over a rotting log and watching in abject wonder as hundreds of thousands of crawling and slithering things creep away; at the end you’re left feeling like you’ve seen something you shouldn’t have, something that was too captivating to turn away from.

In part, this can be attributed to director Terry Zwigoff’s indefatigable dedication to the film, a film no other director could have made. As longtime friends and bandmates, Crumb and Zwigoff’s relationship is important, as it points to the dedication Zwigoff brought to the project (which took nine years to complete); Crumb is a documentary of one friend by another.

This is perhaps why Crumb himself is so open and giving to the camera; his candidness is almost startling. For example, in one of the opening scenes, we see him inking sketches of his high-school crushes in his notebook—it’s an enthralling scene, and one we feel privileged to watch.

Indeed, the entire film is made up of scenes like that one. Zwigoff talks with Crumb’s mother and two brothers, and we begin to piece together Crumb’s childhood and, in the end, what makes him the man he is.

We hear “experts” slather praise on his art and, at the same time, we hear it dismissed. We see Crumb’s attitude toward his fame and how he copes with it; we see him as a parent, as a child, as an icon. What Crumb does best, though, is allow us to make up our own minds. We’re left to decide for ourselves who this man is—is he a hero? A pervert? A genius? We’re able to psychoanalyze him—we feel obligated to—and, in doing so, Crumb leaves you with a conclusion that is all your own.

Like the films of the great documentarian Errol Morris (Gates of Heaven [1978] and Fast, Cheap & Out of Control [1997], to name only two) Crumb is a success not because of shocking evidence uncovered or because its information is inherently pertinent to us (as a Michael Moore film might be) but because it is so intangibly bizarre.

Zwigoff thrives on the quirks of human nature here, and it is precisely because of the abstract nature and the wonderful uniqueness of his film’s subjects that we are able to derive our own personal meaning out of Crumb.