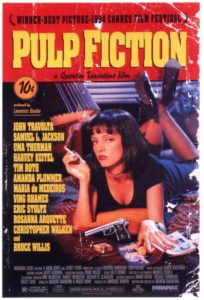

Pulp Fiction

5/5

Pulp Fiction (1994) was the last film that was both truly original and widely successful. You can moan all you like about Mulholland Drive (2001), and you can say, “Hey, wait—Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) was insanely original!” I’ll even remind you about Spirited Away (2001) and Synecdoche, New York (2008), two ingenious and innovative films. But not one of these movies challenges Pulp Fiction in its almost biblical uniqueness and impact on society.

It’s a rankling assertion that Pulp Fiction is unparalleled in originality. It seems almost sacrilegious, but hear me out.

Pulp Fiction’s release marked the end of film’s post-modern heyday—the period from the early ’70s to May 12, 1994 (the day Pulp Fiction was released), when films like The Godfather (1972), Taxi Driver (1976), and Blue Velvet (1986) were reconstituting older films to create interesting and innovative conglomerative pieces.

Pulp Fiction soundly ended this phase because it recycled film and TV of the past and also reconstituted post-modern films themselves. Because post-modern films were supposedly making comments about society, Pulp Fiction consumed society itself and presented back to the people exactly what the people had presented to it (and in the process proved there is nothing beyond post-modern).

Really, it’s all in the title—Pulp Fiction consists of a series of chopped-up, fictional, often vulgar, and wholly engrossing segments that are unpredictably tied together into a web of pure entertainment. And it’s Pulp Fiction’s transcendence of plot (just try summarizing it) that proves its originality.

However, without cultural acceptance, the movie would merely be one more on the great pile of “critically acclaimed” films—films that are fantastic if you can put up with their idiosyncrasies. Pulp Fiction, however, landed with aplomb in 1994; it sold truncated culture back to the people.

And yet, unlike many post-modern works critiquing society—The Simpsons, for example—Pulp Fiction is not cynical. In fact, it celebrates the very things that it’s critiquing: violence for the sake of entertainment, infatuation with appearances, and the self-awareness of pop culture. And because it eschews condemnation of society’s tendencies, it’s worth its weight in memes.

Comparing Pulp Fiction to the Bible is really quite apt—both are composed of stories passed forward from the past, both take liberties with reality for the sake of deeper meaning, and both have saturated modern-day society to the point of ubiquity. Most importantly, though, neither has been replaced or surpassed since its respective release.