Vincent Gallo’s Billy Brown is pathetic. He whines and shouts and contorts in frustration. He moulds his expression into a man-child tantrum in an abrasive defense to care. He entered prison this way and he exits it the same. Volatility was learned and loneliness is the by-product. Indeed, Billy needs what he isn’t owed: a tender embrace.

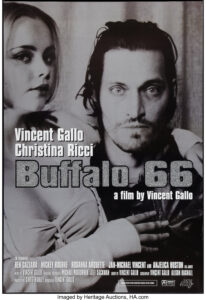

In Buffalo ’66 (1998), Layla (Christina Ricci) is mandated to act this part of an adoring wife. Hours after being released from his five-year sentence, Billy kidnaps her. Walking in during a tap-dancing class to use the washroom, he snatches her to play make-believe for his parents. He had lied to them, of course, that he had a beautiful woman, and that in his sudden five-year absence was not locked away but was a real deal CIA agent—a cover that functions as well as his temper. She must go along with this if she wants to live, he says.

Yet, Layla seems still in control. She pities him, really, and performs with gusto for his parents regardless of their interest. At Billy’s family home, sitting at the table in the middle of a room shrouded in Buffalo Bills merchandise, dad (Ben Gazzara) is just as volatile and mom (Anjelica Huston) is too invested in the Bills game to find much care for his return home. She wishes she never had Billy, she says, because that way she wouldn’t have missed their only championship win in 1966. In the abundance of bobbleheads, jerseys, trophies, and football helmets, there is only one photo of Billy tucked away. We begin to understand Billy’s insecurity and where it derives—he is malnourished of any love.

The film pours with a creative flair unique to director and actor Gallo. Flashback scenes obscure the present like patchwork. They cover the frame with excuses for poor conduct when we zoom in and out of a young Billy. We see his dejection. We see why he went to prison: in a naive whimsy he bet $10,000 that he did not have on a Bills win. And just like every year since 1966, they didn’t. The bookie arranged a deal. Hence, prison. We notice, perhaps, a humility that has since disappeared.

Interpretations of the film are in multitude—a meditation on Stockholm syndrome, a love story, a tale of profound loneliness only bettered by the kindness of a graceful woman. They all clash, but they all have opportunity for validity. It doesn’t so much matter, anyway—the film’s sort of magical realism works better without the concrete. The ending is just as discursive (although less so than Gallo’s Brown Bunny, of course) at leading the narrative beyond the screen. Are her eyes open because she is content with their mutuality or because she no longer finds the relationship enthralling? Is she frightened? Has his hostility been treated and cured? How Buffalo ’66 mesmerizes its audience is its lack of answers.