On each floor of the Hudson’s Bay department store, luxury goods stale under fluorescent light. It prides itself on DKNY and Calvin Klein. It offers Levi’s and Breville and the Wonderbra. They stew in uninhabited air and have mildewed. They wait for buyers who never show. A scuffed white hue, presumably pampered many decades ago, cloaks the linoleum, the drywall, the furnishings, and the formerly manicured accessory displays. It is the oldest corporation in North America and shows its age unforgivingly. The Bay, as it is likewise known, swelled its colonial empire unto 80 multi-level commercial spaces, but by mid-June will liquidate its entire miscellaneous inventory to vacate all locations come the end of the month. By July it will join Sears, Zellers, and Nordstrom in their undoing.

The department store, as it was in 1796 for Harding, Howell & Co’s Grand Fashionable Magazine at 89 Pall Mall in St James’s, London, catered itself to the everyday fashionable white woman. By design, it afforded her room to meander out of the home, where she could shop without men’s company, tended after only by familiar middle-class sales associates. Shopping, ergo, fused with the social space—she sees perfume samples and knows she’s in good hands. But it was only by the turn of the 20th century, shaped by the standards of the Industrial Revolution, that the status of the department store was made official to its brand: this was the most efficient manner to shop. The five-, six-, sometimes eight-storied palaces not only offered things, the kind that one needs to maintain the home and one’s self, but stuff, the kind of excess.

But it isn’t the efficient way now; the numbers disprove it. The excess we’re after isn’t found at Sears or Zellers or even The Bay, we figure, and its accessibility is outmatched. Asked why they believe The Bay has been forced to close its doors, final wandering customers insist the department an outdated model. The store, they say, just didn’t keep up with what is now the demand. The demand, of course, being efficiency. The accusations of an archaic institution aren’t wholly false, of course; Karen Scott doesn’t very well mimic what’s in fashion at the rapid pace trends cycle, and the worn escalators undeniably cannot supply the same comfort of one’s own home. The gaze for efficiency finds desire elsewhere: the internet, and the internet doesn’t require gas to reach. Indeed, the internet requires very little of a consumer and the consumer is omitted entirely from the operation. By its claim, and what’s been collectively assumed of it, online shopping is the newest, fastest, frictionless way. This is why we use it instead of finding parking, we are giddy to say.

Still, most times, we must wait many days for our stuff once the order is placed. Surely the department store outdoes its competitor there: faster. Surely, then, we must see the value in making the trip, paying none for shipping. But, even so, that still doesn’t agree with our standard of efficiency; what we are after is not the productive convenience of accessing goods but the convenience of forgoing the ritual. The convenience we now seek, some centuries later, extends not only to the immediate five-metre radius, from the hand to the iPhone, but to the practicality of alienation.

It is easy, undemanding, to shop without a knowing conscience. Feeding the internal informed buyer sacrifices the cultural tradition of mass consumption. Feeding, instead, the detached buyer, the one who is too naive to consider child labour or environmental costs to choose their consumption wisely, allows us the rash freedom we cherish to purchase without guilt. With a conscience we set limits, do what we must to reduce our harm. The experience of the department store disobeys this principle—it begs us to confront the tradition we strongly uphold. On my farewell visit to Hudson’s it is glaring, it is a crime scene of capitalist merchandise. On a rack of clearance dresses, one of many dozens, dazzling neon colours tightly squeeze against one another as to save room on other stands for more sporty-looking button-ups and denim of all shapes. The fabrics line up like contorted bodies waiting to be relocated. It begs for my repentance, and to hide one must find what isn’t there: a functioning elevator.

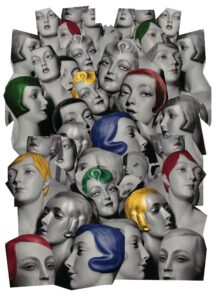

We remove ourselves easily when online. And most times the interface for shopping websites (Amazon, Temu, Shein, et cetera) succeeds well in hiding the very tangible warehouse behind trendywear. When the product is streamlined, sometimes even “picked for you,” there is no need to see the 150,000-square-foot assemblage of stock. That is preferred, of course, for both the consumer and the corporation, as to see the mounds of polyester, silicon, spandex (plastic) is to see the number of tired bodies and oceans desperate to rid themselves of the stuff-manufacturing industry. Within this newest shopping arrangement, there are only smiling models, rather than these exploited figures, to do the bidding.

Perhaps most crucial to the decline of the department store’s allure, however, is the willingness and impulsivity we have to opt out of all interaction with one another. Shopping in excess while alone there are no checks or balances to weed out the rabbit-shaped ice trays or the illuminating shower heads or the beer-themed briefs or the boho-chic recliner chair that we may feel, by its novelty, eager to buy. In the department store, you are watched and then recorded—if not by a sales associate with a keen eye, then by security with its camera. Your purchase, however intimate, attracts assumptions. Entering Hudson’s Bay alone, I was addressed and considered; my existence there, unlike what could be of the AliExpresses of the internet, was extracted from the scuffed white hues and neons. And as I kept to myself, maintaining the alienation we have decided is now world order, friction between my consumption and the sales associate’s pay cheque, which seeks commission to provide sufficient income, chaffed loudly between our small talk.

Indeed, it is this way that the department store model is, as the Baby Boomers roaming the home-goods floor had said, outdated. Our pull to exist indoors, in solitude from others, has swiftly increased. To exit the home, we are forced to pay our dues: make the small talk, look one another in the eye and say, Yes, that is all. The idea that these interactions lay the foundation for humanizing our community seems never to be addressed. The department store, in its large stature, leaves little to humanize but those inside. And so the question is not why The Bay will close this June, but why we’ve decidedly left the institution to decay.

Depending on whoever you talk to, it either was or wasn’t predictable. The North American temptation for individualism, shaped by the Industrial Revolution, has bred new generations of buyers who fear the stranger. Our desire for isolation conflicts with the very origins of the department store: the social space to commune. Of course, today’s department stores don’t maintain this same glamour and hospitality. Almost on purpose it seems that The Bay closed down. The unkempt and unattended stretches between sales counters—all that is now left—is not new to the store’s look. It’s understandable, then, why many assert this as one reason for dwindling turnout. But while that may be true, its cause is not simply a natural progression—our draw elsewhere, where to be social isn’t standard, manufactured its demise.

Travelling up and down the escalators a month from Hudson’s permanent closure I saw that clearly. I waited for a voice but heard only the curated radio until reaching the highest floor. The woman behind the Chanel counter asked how I was, in formality, but I couldn’t be too sure what state I was in. In The Bay, it is always mild. On this day, however, the tone on the fifth floor required my sensitivity. The institution has been beaten by the ubiquitous urge to consume in private. The impulse to abandon our conscience for material fulfillment has never been so frictionless. In formality, I asked her the same.