In a short-winded preoccupation with the legal drama genre, I watched innumerable of its films in the span of few afternoons. This sort of fling happens cyclical and is seldom fruitful in its sophistication—that is, of course, its express purpose. Indeed, to engross oneself in any singular variety of media is a kind of sedation. In forging a truly monogamous commitment with a genre, we are quieted of the tumultuous yammer of the erratic public and we tamper with its affliction on the soul. It could be true that “variety is the spice of life,” and to seek stability fails to nourish a vibrant life, as the proverb suggests. But it could also be true, and I believe this to be the case, that variety impedes on the comfort one is owed.

The legal drama genre performs well this such way. For the most part, legal dramas follow a formulaic template of lawyer turmoil and a predictable prevail (often despite there being much for the case to stand on). In A Time to Kill, viewers are shocked that Samuel L. Jackson in his role as an austere father is freed from prison after killing his daughter’s abusers. But, the film could only ever come to this end, otherwise it would be a disgrace. In The Rainmaker, we are satisfied to see an inexperienced young lawyer, played by Matt Damon, take down Big Insurance. But, really, the defense never did succeed in disproving their malpractice. Fictional courtrooms are designed to appease the good guy and condemn the bad—this is unlike non-fictional courtrooms that ditch what is right for what is quasi-fair. The legal system, the actual kind, has no moral code and its consequences are severe. This is the basis of the 1979 film …And Justice for All, and what sets it apart in the vast library of optimistic storytelling.

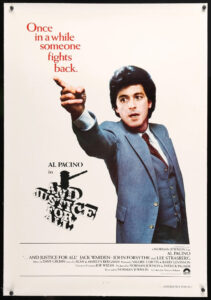

Al Pacino plays the protagonist in the film. He’s a lawyer, a cynical one, a Baltimore defense attorney detached from his work. We see him working on one case and then we see him on another, and he’s having a tough go at all of them. Despite a consensus on all legal ends that one client is innocent (simply put, he was in the wrong place at the wrong time), the bureaucracy of it all stands in the way.

But the worst of it is, and this of course is what receives Pacino’s most disillusioned sentiments toward the legal system, the judge whom Pacino resents has now requested that Pacino defend him in a brutal rape case in which the judge is the accused. What the request then begs is if it is indeed possible to lay to rest the conscience. At what cost does one spare their morals for the institution? How does one exempt themselves from their work? Director Norman Jewison’s …And Justice for All is capable of unravelling these questions and the legal drama as a genre.

The actual legal system, as it stands, demands these answers. And, to its detriment, there aren’t any.